My one liner: How a foremost biochemist became a foremost sinologist, and single-handedly created the Western world’s understanding of China, long before it became fashionable.

15 May 1948. “Science and Civilisation in China. Preliminary plan of a

book by Joseph Needham, FRS. It will be addressed, not to sinologists, nor to the general public, but to all educated people, whether themselves scientists or not, who are interested in the history of science, scientific thought, and technology, in relation to the general history of civilisation, and especially the comparative development of Asia and Europe”.

Needham, a fellow, and subsequently, Master of Gonville and Caius College Cambridge, went on to write Science and Civilisation in China, which is widely considered the foremost work on scientific development in China. He himself wrote 15 volumes over the next 4-5 decades of his life, and further volumes have continued to be published following his death in 1995. Simon Winchester's book traces the life story of Needham and the path by which his work came into being. And through that journey we learn much ourselves about a civilisation that for long periods of history has been far more scientifically advanced than the West. Far more, arguably, than wading through the blogs, commentaries and predictions spewed out by some of today’s “China watchers”.

And just as importantly we learn something about this remarkable man, and the potential of what can be achieved by human endeavour, application, determination, and an openness to foreign ideas and cultures. Needham was after all a specialist in biochemistry. In 1939, before he was 40, he published a book on morphogenesis which was acclaimed by a Harvard reviewer as “destined to take its place as one of the most truly epoch-making books in biology since Charles Darwin.”

A committed socialist throughout his life, Needham was selected by Britain’s academic community at the start of the Second World War to go to China and assist with a programme of reconstruction of China’s academic and scientific institutions, following the devastation wrought by war with Japan. And from there he didn’t look back. Already familiar with the Chinese written language through lessons from his friend / colleague / lover / concubine / and eventually in 1989, wife, Lu Gwei-djen, Needham embarked on a relentless pursuit of knowledge about China.

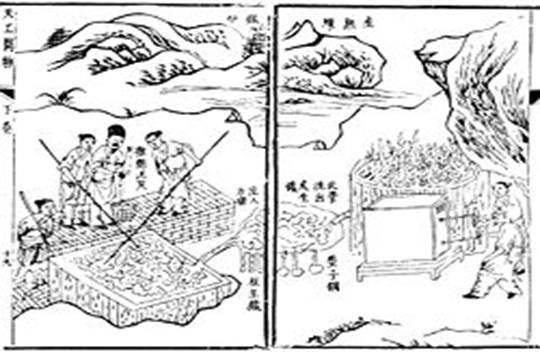

The appendix of Winchester’s book lists “Chinese Inventions and Discoveries with Dates of First Mention”. Here are a few: Algorithm for extraction of square roots and cube roots: 1 AD; Ball Bearings 2AD; Blood, distinction between arterial and venous: 2BC; Compass, magnetic for navigation: 1111AD; Grid technique, quantitative, used in cartography: 130 AD; Melodic composition 475 AD; Numerical equations of higher order, solution of 13C

AD; Pi, accurate estimation: 3AD; Printing, with woodblocks: 7C AD; Rocket arrow launchers: 1367 AD; Soybean, fermented: 200 BC; Watermills, geared: 3C AD. As Needham said: “The mere fact of seeing them listed brings home to one the astonishing inventiveness of the Chinese people”.

Written in the style of a novel, Winchester's book puts us into Needham’s shoes as he travels to the what were at the time some of the most remote parts of the planet, for example his Silk Road journey, in a truck which was a converted Chevrolet ambulance. As he visits academic institutions, government offices and archeological sites he assembles a collection of original papers and documents detailing every facet of Chinese scientific and technological progress, and on returning to Cambridge after the War, proceeds to catalogue these, leading to the 1948 book plan.

There is of course his personal life, sympathetically and empathetically described. His devoted wife Dorothy, who is accepting of the open nature of their marriage, is a friend and confidante of Gwei-djen. Needham’s political views, bordering on communism in an age of McCarthyism, and his sympathies with Mao’s regime, lead to frequent run-ins with the political and academic establishment.

But we are left with the enduring notion that the pure pursuit of knowledge, and the desire to open that knowledge to society at large through painstaking effort, prevails in the end. That a scientist trained in the supposedly physical precision of Western enquiry can be so open to the ancient scientific traditions as the genesis of his work, is a salutary lesson for all of us:

“Heaven has five elements, first Wood, second Fire, third Earth, fourth Metal, and fifth Water. Wood comes first in the cycle of the five elements and water comes last, earth being in the middle. This is the order which heaven has made. Wood produces fire, fire produces earth (ie. as ashes), earth produces

metal (ie. as ores), metal produces water (either because molten metal was

considered aqueous, or more probably because of the ritual practice of

collecting dew on metal mirrors exposed at night time), and water produces wood (for woody plants require water). This is their ‘father and son’relation. Wood dwells on the left, metal on the right, fire in front and water behind, with earth in the centre. This too is the father and son order, each receiving the other in turn...As transmitters they are fathers, as receivers they are sons. There is an unvarying dependence of the sons on the fathers, and a direction from the fathers to the sons. Such is the Dao of heaven” From Chun Qiu Fan Lu, by Dong Zhongshu 135 BC. Quoted by Needham in Vol II, 1956.

Here is the wikipedia link to the author. There is no wikipedia entry for the book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed