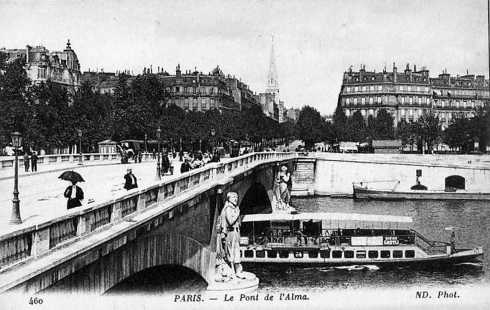

In the opening scenes the protagonist Ravic first meets his lover-to-be Joan on a cold November night in the shadows of the Pont de l’Alma in Paris after literally bumping into her, sensing her distress about some event unknown, and taking her home with him. Only to find out shortly afterwards that her (now-former) lover has just collapsed and died.

Erich Maria Remarque is “of his generation”. His works reflect a life that straddled two world wars. Arguably his more famous work is All Quiet on the Western Front (note to self: re-read). Remarque’s themes are oppression, and Ravic, a German-speaking Czech, is the epitome of the stoical existence of those who fled the Nazis.

“Don’t you know that refugees are always as stones between stones? To their native country they are traitors. And abroad they are still citizens of their native country”.

Ravic, a refugee in Paris is a doctor, a surgeon. As an illegal, he cannot work officially, so he works as a “shadow” surgeon, performing operations for lazy or incompetent French practitioners who pay him a small cut of their fee – the patients of course, do not notice: they are under the knife by the time Ravic appears.

The title Arch of Triumph is for me an ironical metaphor for what was about to sweep across Europe, a tidal wave of oppression, reaching its apex as it converges on the actual Arc de Triomphe. And I think Remarque paints this scary vastness exquisitely in his descriptions of the grey Paris cityscape:

“The Arc de Triomphe emerged, gray in the silver downpour, and disappeared. The Champs Elysées with its lighted windows slipped by. The Rond Point smelled of flowers and freshness, a gay-colored wave amid the uproar. Wide as the ocean dawned the Place de la Concorde with its Tritons and sea monsters. The Rue de Rivoli swam closer, with its bright arcades, a fleeting glimpse of Venice, before the Louvre arose, gray and eternal, with its unending courtyard, all its windows dark. Then the quays, the bridges, swaying, unreal, in the gentle rain. Lighters, a towboat with a warm light, as comforting as if it concealed a thousand homes. The Seine, the boulevards, with busses, noise, people, and shops. The iron fences of the Luxembourg, the garden behind them like a poem by Rilke. The Cimetière Montparnasse, silent, forsaken.”

Some explored in rich deep colours, others with rapid brushstrokes conveying the essential traits that mark them out. This of Veber, one of Ravic’s more honourable French “clients”:

“It was Veber’s invitation. That tinge of pity in it. To grant someone an evening with a family. The French rarely invite foreigners to their homes; they prefer to take them to restaurants. He had not yet been to Veber’s. It was well meant but hard to bear. One could defend oneself against insults; not against pity.”

Or the young lad Jeannot, who fulfils a kind of jester role in the novel, when he wakes up in the operating theatre after a car accident:

“"The leg has been amputated,” Ravic said. “Above the knee or below the knee?” “Ten centimeters above it. Your knee was crushed and could not be saved.” “Good,” Jeannot said. “That makes about fifteen per cent more from the insurance company. Very good. An artificial leg is an artificial leg, whether above or below the knee. But fifteen per cent more is something you can put into your pocket every month."”

Indeed dark humour suffuses the novel, often as a means of illustrating the politics and attitudes of the era, a method perhaps oddly reminiscent of the sardonic, mocking style of Molière:

"“Veber,” he said, “you are a magnificent example of the convenient thinking of our time. In one breath you are sorry because I work illegally here—and at the same time you ask me why I don’t rent a nice apartment—”"

In amongst all of this depth of character, stoical acceptance, gritty greyness and political upheaval you may be thinking that the plot is somewhat incidental. And in a way it is. Yes, there is a love story. Two actually. And a holiday to the south of France to get away from it all. And a deportation.

Together with an opportunistic exacting of revenge for an old wrong.

There are historical lessons too, and perhaps those who eagerly call for breaking up the current European political construct should reflect on how recent it is that is was so hard just to move from one European country to another:

"“To Italy? The Gestapo would wait for me there at the frontier. To Spain? The Falangists are waiting there.” “To Switzerland.” “Switzerland is too small. I have been in Switzerland three times. Each time the police caught me after a week and sent me back to France.” “England. From Belgium as a stowaway.” “Impossible. They catch you in the harbor and send you back to Belgium. And Belgium is no country for refugees.”"

Also a timely reminder that complex challenges await our current crop of leaders.

And so ultimately, you cannot escape the fact that this is a political novel, immersing you at each turn of the page, every location, every interlocution, in the reality of what it was like to live at the time, and why:

"“Suddenly Ravic had the feeling that all the misery of the world was locked into this ill-lighted basement room. The sickly electric bulbs hung yellow and withered on the walls and made everything seem even more disconsolate. The silence, the whispering, the searching of papers which had already been turned over a hundred times, the re-counting of them, the silent waiting, the helpless expectation of the end, the little spasmodic acts of courage, life a thousand times humiliated and now pushed into a corner, terrified because it could not go on any farther.”"

Here is the movie based on the book

And the Wikipedia link for the book is here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed