We know intuitively that our minds can be “trained” so that we become an expert in something, or maintain our mental agility (think Sudoku, or those Nintendo puzzles designed for old codgers). Neuroscience is an evolving discipline, and research has shown that we can take this intuition much further.

It goes something like this.

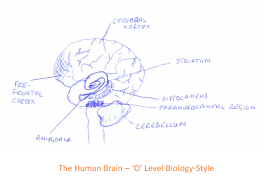

Our personality can be described by six Dimensions of a person’s “Emotional Style” – we sit at some point on line between two extremes for each of those Dimensions, and the combination of all those points, in essence sums up to form our personality. Now, here’s the interesting bit. Which part of the line we sit on with respect to each Dimension depends on either the activity in, or physical properties of, a particular part of the brain.

So what, I hear you ask. We are born with particular brain characteristics, and therefore our “personality” is determined by genetics and that’s it. End of story.

Not so, according to the authors, Richard Davidson (a neuroscientist) and Sharon Begley, a science writer.

Davidson has spent over four decades researching this, and reckons that the size, shape and activity of the various parts of the brain can be changed by “exercise” in the same way that we might change our body shape and fitness by

going to the gym. In other words the brain exhibits neuroplasticity.

The implication ? We can reconfigure our own brain in order to change our location within each Dimension of Emotional Style, and hence alter our own personality over time. Nurture can override nature, in other words.

The book concludes with practical actions we can take in order to reconfigure the brain, ranging from different styles of meditation, to targeted social training “drills”. It also provides possible ways to treat “disorders” such as depression or autism.

What are the six Dimensions of Emotional Style ? They are: (1) Resilience Style (how quickly or slowly do you shake off a setback ?); (2) Outlook Style (broadly, are you an optimist or a pessimist ?) (3) Social Intuition Style (are you good, or bad, at reading visual, aural and oral clues from other people and hence gauging other people’s emotional state ?) (4) Self-Awareness Style (are you intensely self-aware of physical cycle and states of your own body, and are able to relate them to changes in your own mood and behaviour, or alternatively do have difficulty in understanding why you behave the way you do ?); (5) Sensitivity to Context Style (how often, or not do you adapt your actions or behaviour to current social situation ?); (6) Attention Style (how easy or difficult do you find it to focus on a particular task, rather than letting your thoughts or attention wander ?).

An example. Social Intuition. Guess who this is:

“I ushered him to a quiet table [to] get waiters to bring him lunch, [but] he would have none of it. Maroon robe swirling, he walked up to the buffet table, took a plate, and waited in line to serve himself like everyone else – attracting no small number of stares, but even more smiles of appreciation that this Nobel laureate, head of the Tibetan government in exile, best-selling author, and spiritual leader was waiting his turn for poached salmon, rice pilaf, and a Weight-Watchers nightmare of desserts like everyone else. Social Intuition, indeed.”

Note, the Dimensions of Emotional Style are a continuum and each person sits at some point on the continuum for each Dimension. Note also that for each Dimension there is not one “good” extreme and one “bad” extreme. Take Self Awareness. At first blush you may think it is good to be highly Self-Aware. It means you can quickly recognise when you are angry, sad, jealous or afraid, and can relate this to emotional cues within your body. But, taken to the extreme, “someone with very sensitive emotional antennae for his own feelings who observes the pain of another will feel that person’s anxiety or sadness in both mind and body –experiencing a surge of the stress hormone cortisol, for instance, as well as elevated heart rate and blood pressure.”

As a supplement, they advocate techniques originally developed by Giovanni Fava (University of Bologna, Italy), called “well-being therapy”, which also strengthens the Pre-Frontal Cortex to ventrial Striatum link. Broadly, each day, write down positive characteristics of one or two you know, express gratitude regularly (and look into people’s eyes when you say “thank you”), and compliment other people on a regular basis (again, looking into their eyes when you do so).

What I like about this book is that it leads you through the link from the scientific to the practical (as Davidson says: “I am admittedly biased, but I believe that any program that purports to alter something as fundamental as Emotional Style simply has greater credibility if it is grounded in neuroscience). And it leads us through the evolution of the research, from its slightly rickety days in the early 1970s (electrodes strapped to the head monitoring dream activity in volunteer students, with results recorded on polygraphs) to 21st century fMRI analysis in highly controlled environments.

We learn how early science and philosophy contributed. Charles Darwin’s 1872 book “The Expressions of Emotions in Man and Animals”, emphasised the instinctive signs of emotions, particularly facial expressions, hence providing an indication that different emotions must be linked with distinct physiological profiles. Or Carl Jung’s autobiography, entitled Memories, Dreams, Reflections, containing the first observations about introversion and extraversion as traits, and speculating about psychological and physiological differences among people of each type.

And there is alot about Buddhist Monks. Richard Davidson tells of his meetings with, and subsequent co-operation from, the Dalai Lama in collaring monks (the “meditation Olympians”) to participate in medical trials on the effects on the brain of different styles of meditation. Initial attempts to get older mountain-dwelling monks in Dharamsala to participate “on-location” were, as hilariously recounted, a complete disaster. But persistence paid off, and younger, more outward-looking monks did eventually collaborate in studies in the USA, leading to findings that prolonged meditation did increase levels of “neural synchrony”, a phenomenon whereby neurons from different parts of the brain fire off at exactly the same time, a process which research apparently demonstrates will typically make cognitive and emotional processes become more integrated and coherent.

This is a difficult area of science, and has been tackled well. Should you adopt the conclusions and recommendations in order to develop your personality in the ways that are proposed ? Well, the approaches suggested are hard work. And it would be difficult for a layman to verify the scientific research that underpins the conclusions, so you would have to take it all at face value, and hence it would be somewhat of a leap of faith. But then, we don’t read scientific research papers before joining a gym and doing physical exercise. So perhaps this is no different.

There is no Wikipedia link for this book. The link to the author's website is here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed