The Gafin principle: Every criminal gets caught. Every criminal gets caught. The Gafin principle measures whether or not it was worth it. As an example, a Mr Matthews is convicted for 5 crimes, for which he made £500 each. And he serves five years in prison, or approximately 250 weeks. So his weekly earnings from the jobs turn out to be £10 per week. Which he could have earned in any risk-free non-criminal job. So, under the Gafin principle: the crime isn’t worth it.

I like Danny King.

His Kindle books are riddled with errors, grammar, syntax, spelling, the lot. I have no idea whether the print books are the same, but I assume there is some publisher quirk around this.

But it really doesn’t manner. Mr King is an honest author, whose books do what they say on the tin. Most relate to the English criminal underworld, ranging from petty to master criminals. Tales hilariously told, and formulaically set up to put the reader firmly on the side of the burglar, thief, pickpocket, schemer – we are naturally emphatic with characters who are laughably pathetic. Great reading when you have a couple of hours to kill and really don’t want to engage the brain.

I have chosen to review School for Scumbags.

You know you are on to a winner with the opening quote of book, from the 17th century by Jean de la Bruyère:

“If poverty is the mother of all crime, lack of intelligence is its father”

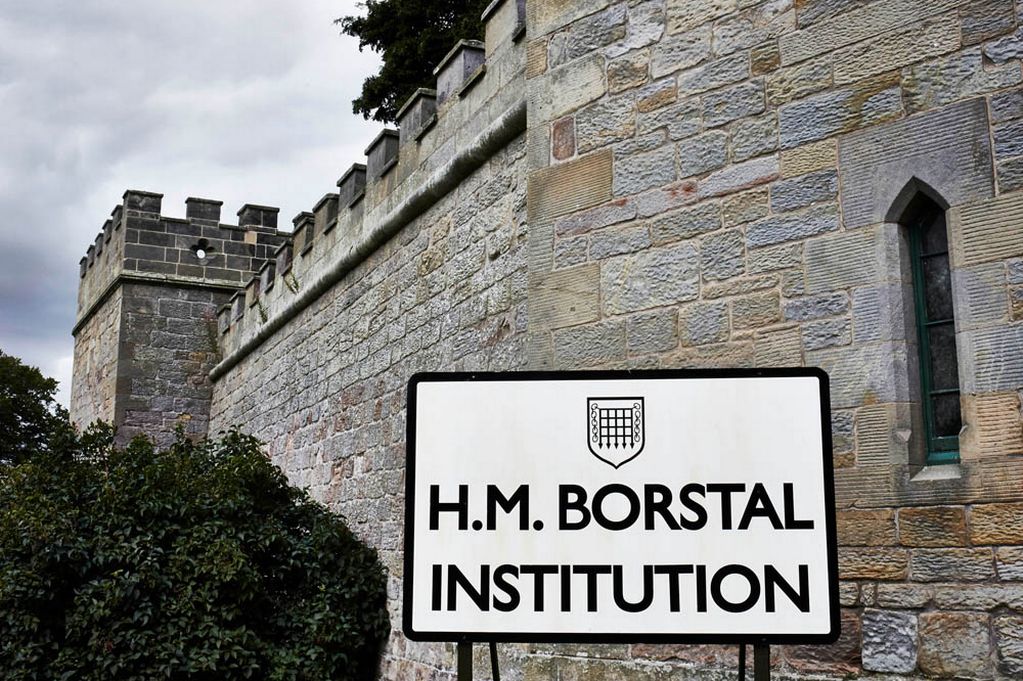

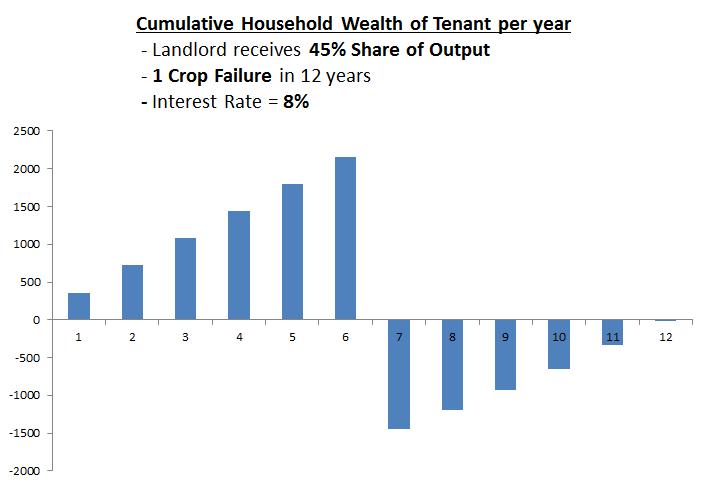

And the teenagers at school for scumbags need a lesson in probability and expectation so that they can understand which crimes are worth committing. “Here at Gafin we take a different approach. We educate young men about crime, show them the effects of their actions, the consequences of indiscriminate robbing.” Gafin, run by Mr Gregson, Mr Fotheringay, Mr Sharp, and lovely and flirtaciously delicious Miss Howard, being the outer-London boarding school where a bunch of teenage delinquents have pitched up (or rather have been sent to by divers despairing parents).

Put these 20 or so young layabouts in closed environment together and they will sound find ways to steal of each other, steal off the school, engineer perfect crimes, protect each other, grass on each other, physically assault each other. Each lad with his own distinctive personality, the schemer, the fat kid, the arsonist, the neanderthal.

The protagonist is a young lad called Wayne Banstead (“Banners”), who being of above average intelligence, ends up being the ring leader in most of the capers. Including a hilariously rigged football tournament where parents are invited to witness the progress of their young angels and also to place “bets” on the likely winners.

But it turns out that the Gregson, Sharp, Fotheringay and Miss Howard have a dastardly plan. They have devised the ultimate heist, and one that most definitely does pass the Gafin principle.

“Gregson told me to go and nick something in the gift shop…Anything, it didn’t matter. ‘Just nick something,’ he said, ‘and make sure they see you do it.’”

And then a period of intensive training for the big day. No detail left to chance, intensive training, team spirit and camaraderie, removal of a couple of bad apples from the team, and hence from the school.

Each boy clear what his role would be. And who would suspect a bunch of teenage schoolchildren of actually walking out with the stash ?...

So, in keeping with the standard formula of the heist story e.g. [insert your favourite heist movie here], the reader finds himself egging on this disparate bunch of young budding criminals to successfully complete the job.

Naturally there are twists and turns along the way, some people do get hurt, and I won’t say what happens to the treasure, but it’s a fun yarn full of chuckles and giggles.

There is no Wikipedia page for this book. The Google Books link is here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed