“[T]he Zeitgeist (“spirit of the age”) of the early twenty-first century is being shaped by a profound change of paradigms, characterized by a shift of metaphors from the world as a machine to the world as a network. The new paradigm may be called a holistic worldview, seeing the world as an integrated whole rather than a dissociated collection of parts”

The Systems View of Life - A Unifying Vision (Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi) is the kind of book I wish I could write. As the industrial age, which began in the period of the European Enlightenment, draws to maturity through the end of the 20th century and beyond, its very fruits have given humanity the tools to move beyond the industrial and mechanical, and into a higher conception of the nature of existence.

Thus we have the insights of quantum physics and fractal mathematics which were only made possible by going through the Newtonian / Cartesian phase. Or the interconnected, networked world that is forming today, that came about through incremental phases of industrial, machine-based progress. The recent giant leaps in computing power that today enables us to study and model complexity and chaos, leave us perhaps with more questions than answers, but evolved through essentially linear statistical methods over the preceding 200-years.

Where Capra and Luisi take us therefore, is into a place that we I think, already know to be instinctively know we need to be. Namely that as a society we are perhaps grown up enough to be able to once again emphasise the qualitative over the quantitative, the observation over the explanation, the process rather than the outcome. The prize, they argue, is a great one:

“As we move further into the twenty-first century, transcending the mechanistic view of organizations will be as critical for the survival of human civilization as transcending the mechanistic conceptions of health, the economy, or biotechnology. All these issues are linked, ultimately, to the profound scientific, social, and cultural transformation that is now under way with the emergence of the new systemic conception of life.”

Personally I would add a caveat to this: the developed or industrialised world in primed for this transition; the developing world is still undergoing its industrialisation phase through which many hundreds of millions of people are being lifted out of food poverty. Capra and Luisi hint that this can be short-circuited (“The root causes of hunger around the world are unrelated to food production. They are poverty, inequality, and lack of access to food and land”) – my view is that they need to take their time to evolve societally, having now moved away from a land / organic-based existence – they will not need 500 years like we did, but they will need decades. This is important, because the transitions implied in the book will likely remain imperceptible at the level of all humanity for rest of the century.

Moving back to the book itself, the authors do well to delve into science well enough to give the reader a sense of rigour, without crossing the line into incomprehensibility for the layman. A consistent theme is the rationalist, and currently prevailing tendency to break down our existence into building blocks and compartments, whether that be measurements of economic growth, medical diagnosis, legal systems, industrial production. But modern physicists have taught us that at that quantum level “matter” (in the non-technical sense) is fundamentally interconnected and cannot be reduced to infinitesimally small building blocks:

“An electron is neither a particle nor a wave, but it may show particle-like aspects in some situations and wave-like aspects in others. While it acts like a particle, it is capable of developing its wave nature at the expense of its particle nature, and vice versa, thus undergoing continual transformations from particle to wave and from wave to particle…

The discovery of the dual aspect of matter and of the fundamental role of probability has demolished the classical notion of solid objects. At the subatomic level, the solid material objects of classical physics dissolve into wave-like patterns of probabilities. These patterns, furthermore, do not represent probabilities of things, but rather of probabilities of interconnections…

The laws of atomic physics are statistical laws, according to which the probabilities for atomic events are determined by the dynamics of the whole system. Whereas in classical mechanics the properties and behavior of the parts determine those of the whole, the situation is reversed in quantum mechanics: it is the whole that determines the behavior of the parts.”

More obviously upwards - the functioning of the human body; the development of societies and economies; ecological phenomena; the space-time of the universe. Less obviously downwards, but reaching into the spiritual and philosophical (think of the buddhist and other eastern philosophies which emphasise the oneness of zero and infinity).

We arrive here through the property of fractal geometry known as self-similarity. The authors tell us how the inventor of fractal geometry Benoit Mandelbrot demonstrates this by breaking a piece of a cauliflower and showing that it looks just like a small cauliflower. Every part looks like the whole vegetable at every level of scale.

So if such interconnectedness and self-similarity exists at the quantum level, why have we organised our societies in such a compartmentalised, non-holistic way ? The answer set out in the book can be summarised by two phenomena.

First, the focus on responding to, and treating, observed outcomes rather than rather than understanding the underlying processes that lead to those outcomes. An obvious example would be politicians who create new government policies based on “events” rather than a qualitative appraisal of the world around them. Or alternatively the diagnostic approach of modern medicine:

“The conceptual foundation of modern scientific medicine is the so-called biomedical model, which is firmly grounded in Cartesian thought …[T]he conceptual problem at the center of contemporary healthcare is the confusion between the origins of disease and the processes through which it manifests itself…

A systemic approach, by contrast, would broaden the scope from the levels of organs and cells to the whole person – to the patient's body and mind, as well as his or her interactions with a particular natural and social environment. Such a broad, systemic perspective will enable health professionals to better understand the phenomenon of healing, which today is often considered outside the scientific framework. Although every practicing physician knows that healing is an essential part of all medical care, the phenomenon is presently not part of scientific medicine. The reason is evident: it is a phenomenon that cannot be understood when health is reduced to mechanical functioning.”

The second is the sense of connection that humans once had with the physical world, the land, nature and eco-systems, and which has been lost through in the industrial society that we inhabit. This connection is, the authors tell us, real and rooted in science. Indeed that very epitome and oft-cited champion of the rationalist scientific school, Charles Darwin gives us our route back to nature. For at the end of day all living organisms share a common ancestor. Organic and inorganic matter evolved to produce living cells which then evolved to produce water, air and land-borne species, of which we are but one.

“There is nothing more holistic and systemic than this notion of Darwinian biological evolution”

Studies of the number of proteins that form all of life suggest that there around 1014 different types (or 100,000 billion). A lot, you might think. However, the mathematically possible number of proteins that could exist based on chains of so-called “residues”, or amino acids, is 10130. Some of those would be energetically impossible, but even if 1 in a billion of those are “permitted” the resulting number of all possible proteins would be 10120. By way of comparison if the actual number of proteins in existence were a single grain of sand, then all the other possible combination representing those that don’t exist, would be the equivalent of the Sahara Desert. And we still do not understand very much the process by which that “one grain of sand”, representing all of life, was selected, over and above all of the other mathematically possible combinations.

And delving into space-time, planets such as our own, have also been part of a cosmic evolution of the universe, the concept of a universe “pregnant with life”. The authors quote the physicist Freeman Dyson (1985):

“As we look out in the universe and identify the many accidents of physics and astronomy that have worked together to our benefit, it almost seems as if the Universe must in some sense have known that we were coming.”

So where does that leave us and where do we go from here ? Rationalist science cannot yet (and may not ever) give us the answers to the true origins of life ? Does it matter ? Yes, it does matter, One the one hand it matters to adherents of organised religion, searching for a way to become closer to a god as creator.

And it also matters to the finest scientific minds seeking out the origins of life and the universe, whether to through Big Bang or more recent theories. Take Stephen Hawking, in A Brief History of Time, and his binary test for whether or not there is a creator:

“So long as the universe had a beginning, we could suppose it had a creator. But if the universe is really completely self-contained, having no boundary or edge, it would have neither beginning nor end: it would simply be. What place, then, for a creator?”

Capra and Luisi push us to gaining an understanding of the nature of consciousness, and the signposts point to philosophies of the east:

“From our point of view, the apparent dichotomy dissolves when we move from organized religion to the broader realm of spirituality, and when we recognize that both spiritual experience and the mystery we find at the edge of every scientific theory transcend all words and concepts…

[S]cientists [such as Oppenheimer, Bohr and Heisenberg] published popular books about the history and philosophy of quantum physics, in which they hinted at remarkable parallels between the worldview implied by modern physics and the views of Eastern spiritual and philosophical traditions.”

As physicists delve deeper into the material world they come to realise that their own consciousness is part of the unity of all natural phenomena. Mystics arrive there from the opposite direction, with an understanding that outer world is essentially one and the same as the inner world which is their starting point. Thus there is an increasing recognition, observable as we move into a new century that we are “part of a great order, a grand symphony of life”. Every molecule in our body was once part of a previous body, non-living or living, and the same will apply to all life forms that come after us.

Indeed, the authors point out the origin of spirituality. The word “spirit” is derived from the Latin for “breath”, see also the related Latin “anima”, Greek “psyche”, and Sanskrit “atman”. Allowing us to posit that this notion of the spirit, being breath as the source of life, is common across the ancient schools of thought in both east and west:

“Spiritual teachers throughout the ages have insisted that the experience of a profound sense of connectedness, of belonging to the cosmos as a whole, which is the central characteristic of mystical experience, is ineffable – incapable of being adequately expressed in words or concepts – and they often describe it as being accompanied by a deep sense of awe and wonder together with a feeling of great humility”

This, say Capra and Luisi, is the true sense of “ecology” (derived from the Greek “oikos” meaning “Earth Household”) – a oneness with the natural world around us, being a member of a “global community of living beings”, and not interfering with ability of the earth to sustain life. The reader is not surprised at this point that authors take on a quick detour into Gaia theory as well

Modern social networks have the ability to achieve this. Social networks can be (and have typically in the past) used as instruments of control and authority, through bringing together and influencing people of similar mindsets. But in the future they can also be a means of empowerment, dissipating common views about the importance of sustainability, and a systemic or holistic way of thinking.

Examples include: holistic therapies that connect physical well-being to mental well-being; a recognition that an individual’s well-being is determined by diet, and environment and social interaction; an understanding of the self-healing properties of many systems, including the human body and its surrounding ecology; the importance of human and ecological well-being for any corporate entity, arguably over and above its financial and profitability measure.

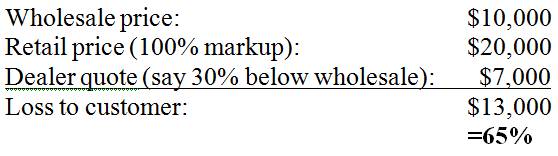

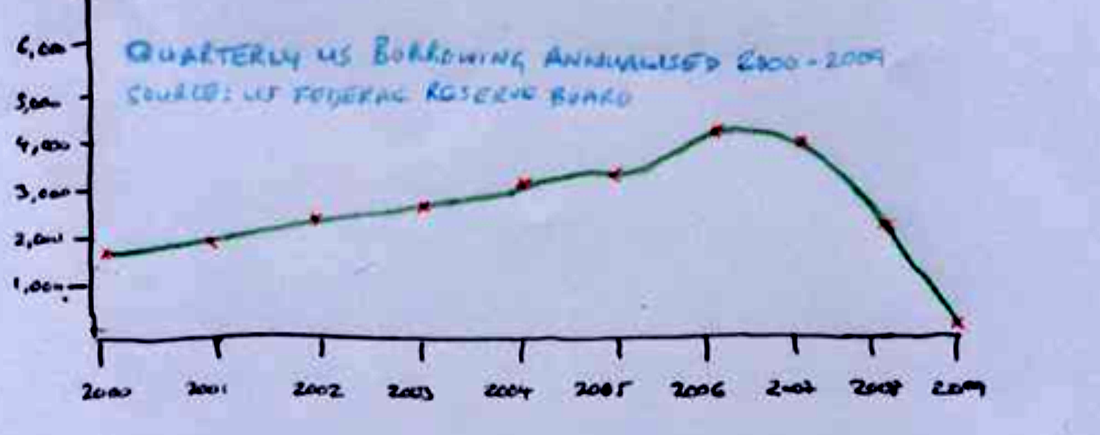

So, the network, technological and philosophical ingredients are in place in the 21st century. What are the policy implications ? Is there some new world order that needs to be created ? The book takes the obligatory diversion through the well-trodden path of the economic and environmental unsustainability of our current existence, culminating in a now-familiar walk-through of the global financial crisis, its causes and effects. We also hear about various bodies, movements and NGOs that have sprung up before and since to address and promote sustainability.

The book then concludes with a number of possible visions for a more sustainable future, and presents a number of overlapping strategies. The authors note in particular that economic globalisation, which has accelerated in the last 100 years or so, is now essentially characterised by a global network of machines (computers, factories, communication lines, financial systems) that are pre-programmed to maximise profit.

The financial motive is the current “human value” which dominates. It would not, they argue, be too much of a leap of imagination to re-programme the machines to have other values built into them. This would also involve moving from quantitative measures of economic growth, such as GDP, to what may be termed “qualitative growth”. Whilst growth is a characteristic of all life, it is not linear and not unlimited – at the same time as some organisms and ecosystems grow others will shrink and release their components which can become resources for new growth. Qualitative growth is “growth which enhances life”. Quantities can be measured, but qualities need to be mapped, and new mathematical and computing disciplines are allowing us now to do this.

Linked to this, the authors contend, should be a programme for corporate reform. The obligation to maximise shareholder return is etched into the contractual structure of a company, its board and the underpinning legal system. The fiduciary duty owed by a company and its managers to its shareholders overrides all other duties. This profit maximising duty makes the same assumption that economists currently do, namely that social costs, resource ownership, ecological sustainability should not be the goal of a corporation. The authors recommend extending or even replacing this fiduciary duty to include the well-being of the corporation’s employees, of local communities and of future generations, and creating new forms of ownership. And arguably this need not be in conflict with a market-based economy.

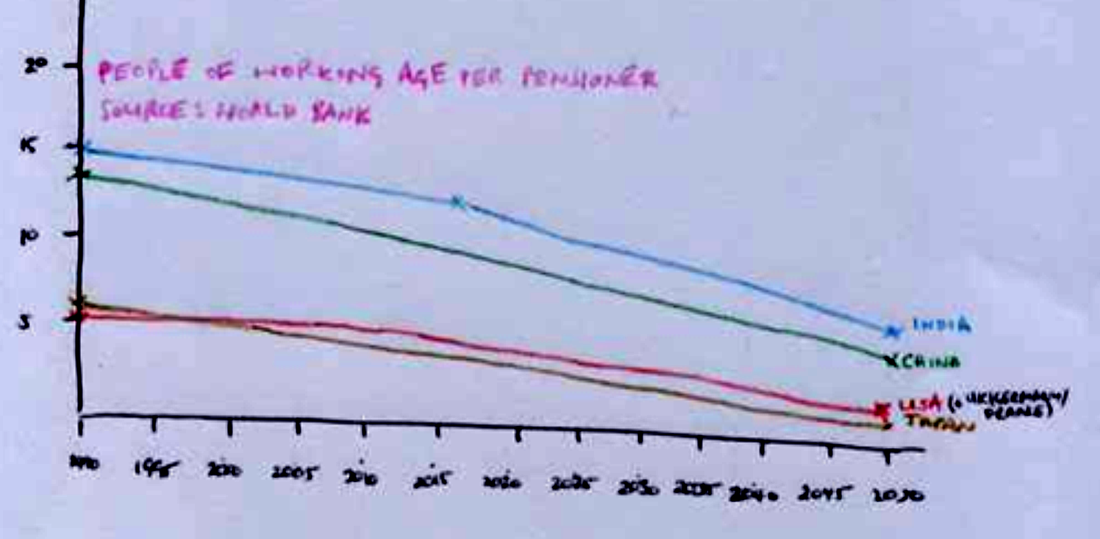

The next area for change is where I am most sceptical – namely a number of suggestions around poverty eradication, stabilising population growth, and empowering of women. The last, in particular is seen to be important as a way of tempering the male, power-based, private ownership-based, accumulative cultures that predominate today, with a more feminine approach: conservation, co-operation, and community. More yin, less yang. I am sceptical not because these aims are not highly laudable (though limiting population growth sounds a tad Malthusian), but because it seems apparent to me, having witnessed the rise of China, the tiger economies and some Latin American countries, that the quickest way to eliminate poverty is rapid industrialisation. As I mentioned, their time for an ecological approach will come, and it will come within decades rather than centuries, but they will have to learn the hard way !

Finally, energy transformation. In particular the systemic view advocates a shift away from coal, oil and other fossil fuels. We are at a moment of perfect technological alignment for an energy revolution, because of advances in both energy and communications technology, enabling the a “Third Industrial Revolution” with five pillars:

- shifting to renewables (solar, wind, hydro)

- transforming building stock into power plants, collecting energy on-site

- deploying hydrogen and other storage technologies

- using the internet to transform electricity grids into “inter-grids”

- transforming automobiles to electric plug in and fuel cell vehicles

The argument is that this can be achieved in the context of a market economy generating viable returns for investors. Couple this with reductions in industrial waste and inefficiency (estimates are that we can save up to 90% of energy and materials currently used in industrial design), and we can become truly sustainable:

“Imagine fuel without fear. No climate change. No oil spills, dead coal miners, dirty air, devastated lands, lost wildlife. No energy poverty. No oil-fed wars, tyrannies, or terrorists. Nothing to run out. Nothing to cut off. Nothing to worry about. Just energy abundance, benign and affordable, for all, for ever”

This is a great book and will get a 5* rating from me on the various book blog sites. I like it because it provides a coherent scientific, philosophical and technological underpinning for the ideas presented. I do agree that we are seeing signs of systemic rather than linear phenomena, and I do think that current conditions can provide the impetus for this transition. What I don’t understand, and I don’t think the authors do yet either, is whether this transition will be itself a systemic process, or whether some top-down “policies” or “new forms of government” will be required to push the process.

There is no Wikipedia entry for this book. The Google Books entry is here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed