‘Deb quando tu sarai tornato al mondo,

E riposato della lunga via,

Seguito il terzo spirito al secondo,

Recorditi di me, che son la Pia:

Siena me fè, disfecemi Maremma:

Salsi colui, che, innanellata pria

Disposando m’avea con la sua gemma’

‘Pray, when you are returned to the world, and rested from the long journey,’ ollowed the third spirit on the second, ‘remember me who am Pia. Siena made me, Maremma unmade me: this he knows who after betrothal espoused me with this ring.’

In his introduction to The Painted Veil, W. Somerset Maugham quotes from Dante to let us know what was the inspiration of the story. The passage is from “Purgatorio” which is the 2nd volume of La Commedia Divina (The Divine Comedy). Pia de’ Tolomei was a gentlewoman of Siena. Her husband suspected her of adultery. He was too afraid of her family and station to put her to death, so instead he took her to his castle at Maremma and left her there, with the plan that the noxious vapours there would kill her off. However, she took too long to die and in the end he had her thrown out of the window.

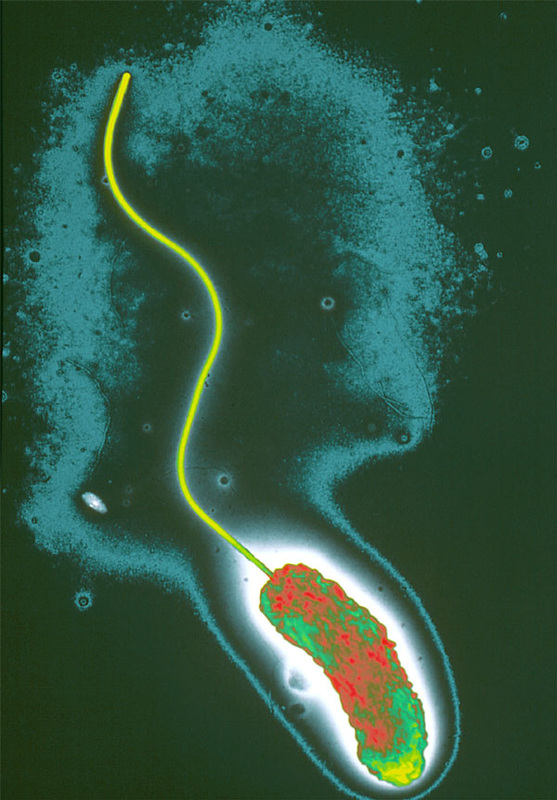

arrival in Hong Kong falls for the charms of the local cad, Charles Townsend. Upon discovering the affair, Walter volunteers a secondment for both himself and Kitty to Mei-Tan-Fu, a fictitious colony deep inside mainland China, which is infested by cholera, in order that Walter can assist in containing the disease. In all probability he is leading one or both of them to death.

In The Painted Veil it is Kitty’s journey from wannabe socialite to a state of knowing, understanding and world-weariness that comes through experiences of sadness, betrayal and human suffering. Her husband Walter himself is considered a nobody in the social whirl of Hong Kong.

“She had discovered very soon that he had an unhappy disability to lose himself. He was self-conscious. When there was a party and everyone

started singing Walter could never bring himself to join in. He sat there smiling to show that he was pleased and amused, but his smile was forced, it was more like a sarcastic smirk, and you could not help feeling that he thought all of those people enjoying themselves a pack of fools.”

A recurrent theme throughout the novel, and one which leads the reader to consistently reflect on the title, taken from a sonnet by the English Romantic

poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley:

"Lift not the painted veil which those who live / Call Life"

Even Walter’s wife hates him:

“It was laughable; he had no sense of humour; she hated his supercilious air, his coldness and his self-control. It was easy to be self-controlled when you were interested in nothing but yourself. He was repulsive to her. She hated to let him kiss her. What had he to be so conceited about?” He danced rottenly, he was a wet blanket at a party, he couldn’t play or sing, he couldn’t play polo and his tennis was no better than anybody else’s. Bridge ? Who cared about bridge ?”

And yet, on the cholera-infested colony of Mei-TanFu, which is where Kitty pays the price of her infidelity, none of these skills are useful. The only Western inhabitants are the Deputy Commissioner Mr Waddington, and the French nuns in a local convent, which also serves as an orphanage for children whose parents have succumbed to the disease.

Here, Walter is in his element:

“He’s doctoring the sick, cleaning the city up, trying to get the drinking water pure. He doesn’t mind where he goes, nor what he does. He’s risking his life twenty times a day. He’s got Colonel Yu in his pocket and he’s induced him to put the troops at his disposal. He’s even put a little pluck into the magistrate and the old man is really trying to do something. And the nuns at the convent swear by him. They think he is a hero.”

The landscapes painted by Maugham take you to the location. As and aside, if you are interested in fin de siècle South East Asia as seen through colonial eyes, I would also highly recommend one of Maugham’s travel books, The Gentleman in the Parlour.

But Maugham’s speciality is conveying Eastern mysticism, and its impenetrability to Western eyes. In The Painted Veil, this mystique is embodied in the Chinese wife of Waddington An aristocratic lady who left her newly impoverished family after the Revolution to devote her life to the

Englishman. And Kitty starts to appreciate the depth and intensity of her

surroundings and their inhabitants:

“Kitty had never paid anything but passing and somewhat contemptuous attention to the China in which fate had thrown her. Now she seemed on a sudden to have an inkling of something more remote and sterious. Here was the East, immemorial, dark and inscrutable. The beliefs and ideals of the West seem crude beside ideas and beliefs of which in this exquisite country she seemed to catch a fugitive glimpse.”

Not that Maugham lets Walter get away with it either. Walter had ‘courted’ Kitty, somewhat ineptly for many months before proposing to her. Indeed such had been his ineptitude that Kitty had not even been sure of his love interest at the moment of proposal. But, she had been on the social scene for several seasons without any (in her mother’s eyes) ‘appropriate’ proposals, and she had accepted more of a desire not to disappoint her mother by not being left on the shelf. It comes back to bite Walter, through Kitty’s infidelity. And Maugham wastes no time in telling us that he was as much at fault as Kitty for marrying her in the first place, and he ultimately pays the price:

“What did it really matter if a silly woman committed adultery, and why should her husband, face to face with the sublime, give it a thought? It was strange that Walter with all his cleverness should have so little sense of proportion. Because he had dressed a doll in gorgeous robes and then discovered that the doll was filled with sawdust he could neither forgive himself nor her. His soul was lacerated.”

Maugham’s language is rarely flowery or sophisticated, and most of his novels are brief. Yet, when you look back on his novels you see that you have gone on a journey with his characters, you have taken on their learning, you have wrestled with their dilemmas, you have lived in their physical space, and you have learnt about their cultural influences.

That is Maugham’s true genius: that you don’t notice all of this until you reach the end of the journey.

The Wikipedia link to the book is here.

There was also a 2006 film which you can read about on Wikipedia here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed