I am surprised this book has not received more attention. This was another of the books I bought during the summer at the closing-down sale of England’s Lane books that I have referred to in various previous postings. A reminder of the rightful place that local independent bookstores should be playing but no longer can in this age of e-books (yes, I do own a Kindle) and online shopping. We are being fed content through our electronic networks, and perhaps we are forgetting how to seek out nice things in the physical world. But that is a topic for another posting.

When the global financial crisis began in 2008, we all started to (re-??) learn some fundamental truths, most of which were of the nature of “not everything can keep going up forever”. In the Impoverishment of Nations, author Leigh Skene introduces us to some further fundamental truths, which are also fairly obvious, but which still don’t seem to be grasped by many policy-makers. This is what can give this book wide appeal. To the layman it can provide a roadmap of where our economies are likely to head over the next few years, and we can draw our own conclusions about what that might mean for us personally.

There is also, I believe, much to digest in this book for the professional investor, since if some of Skene’s global macro predictions are true, then one could use them to construct an international investment portfolio.

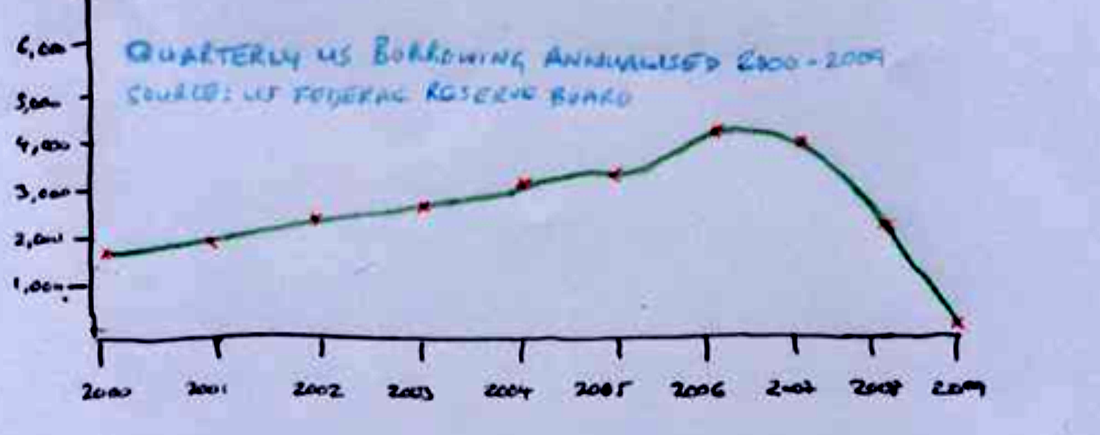

Take for example, Skene’s Fifth Basic Truth (he has 10, which appear in a nice

one-page list at the end): We can’t borrow our way out of debt. Blindingly obvious if you put it like that, and yet, governments (or their Central Banks) are engaging in what is referred to as Quantitative Easing (QE). Basically, this involves a Central Bank printing money which it then uses to purchase financial assets (typically government bonds) from banks. QE is supposed to stimulate economic activity because it increases the excess reserves of banks, so that they can lend this cash out to individuals and companies (particularly small companies). The problem is that this won’t work according to Skene. That is because there is too much private debt already in the economy. The man in the street already has a mortgage and other loans and credit card debt. Hence, a polite “Thanks, but no thanks,” to the offer of additional credit. The chart below which I have hand-copied from Skene’s book illustrates this quite nicely. And if you want to follow up on what has happened in the last three years (more of the same, basically), then take a look at the latest NY Fed Household Debt and Credit Report Q2 2012.

I digress. Back to the book. Where are the upcoming battlegrounds for natural resources ? Well, some interesting perspectives from Skene. First, the world will not run out of oil. Reserves from tar sands and shale gas will provide our energy needs for decades if not centuries to come. That said, this doesn’t mean energy prices fall. Indeed, quite the opposite, geo-political forces are the prime driver of energy prices and are pushing them upwards. Developed-world consumers will adjust by consuming less energy, and hence will have lower living standards. My own view, for what its worth, is that the newly accessible shale gas and tar sands reserves and fracking etc will constitute an in-built stabiliser on the oil price, both upwards and downwards. It is hard to see $200

per barrel without a concomitant large infrastructure investment in new types of extraction. Likewise, you wouldn’t think that much of this new investment would be sanctioned (unless by a government with deep pockets) at $50/barrel-oil. Sounds like a collar on the oil price to me.

Skene thinks, and I sort of agree, that the elephant in the room is Water. Which is a little bit of a mixed metaphor. May I quote from the book, because I can’t express this any better:

“The world’s population has doubled since 1950, but global demand for water is doubling every 21 years. Only 2.5% of the world’s water is fit for human consumption, and two-thirds of that is locked away in icecaps and glaciers. Unlike other commodities, no new water reserves will suddenly be discovered, there is no substitute for water and just about everything and everyone relies on it....Big reserves of fresh potable water lie in underground aquifers that provide more than half of the water in America, up to 80% in Europe and Russia and 25% worldwide. They contain 30 times more water than all the world’s lakes, and hundreds of times more than all the world’s reservoirs...[T]he vast aquifers took millions of years to form and replace themselves extremely slowly...Depletion of global groundwater supplies by an estimated 4% annually...One in ten of the world’s major rivers fail to reach the sea for part of the year, including the Colorado, Yellow, Indus and Ganges...Agriculture uses 70% of the world’s water.”

A couple of slightly negative comments. First, the author then gets all Malthusian on us. He starts by referring to Malthus, and saying that in 1798 Malthus predicted that population growth would outstrip food growth, but didn’t factor in the arrival of the industrial revolution. But then Skene falls into the same trap of suggesting that Malthus’prediction will now come to pass as the world’s population grows to 9 billion.

But who is to say that we are not in the midst of a second, or third or whatever, industrial revolution already ? And anyway population is according to data cited by the author, predicted to peak at 9 – 9.5 billion by 2070. Or maybe we will eat less meat, which is the largest consumer of water. Self correcting mechanisms again ? Second, I wish this item had been included in the list of Ten Basic Truths, as it is an extremely important issue.

The essence of the book is that advanced developed nations have a long period of adjustment to go through which will likely lead to lower living standards after six decades of rising ones. Having borrowed largely for consumption over the last century or so, rather than investing savings into productive assets (Basic Truth 8), advanced nations now find that they cannot borrow more, either at a personal or a national level.

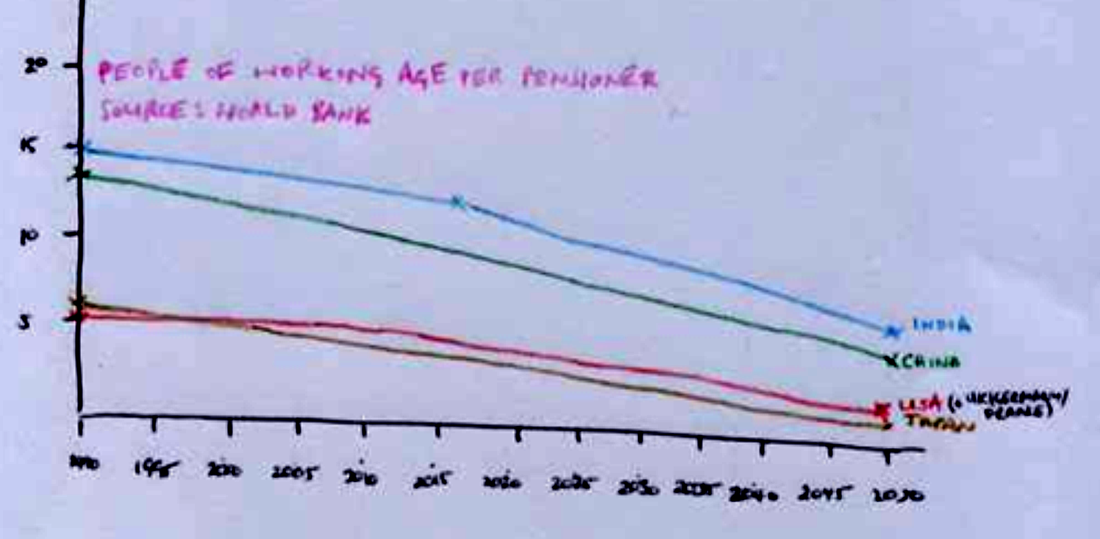

These fiscal burdens will only increase as populations get older in advanced

countries. The number of people of working age available to support each pensioner is dwindling, so either the shoulders of each worker will have to support more burden, or pensioners will need to receive less state assistance. Interestingly, China has a similar problem, whereas India remains in fairly good shape for the rest of the century (see my reproduced chart below).

I would broadly agree with the above analysis, with two exceptions. Advanced economies have one huge “balance-sheet” item which is mostly ignored by economists’ appraisals. That is the Rule of Law. Western legal systems have evolved over many centuries to the point where comprehensive property and legal rights exist with confidence. They are far from perfect (as this previous blog post of mine illustrates), but they do provide a basic foundation for widespread economic and social activity. This gives these countries safe-haven status and will make them a favoured FDI destination.

Which brings me on to why I think this book is of practical relevance. If (as I do) you agree broadly with the conclusions, then it can also inform an appropriate investment thesis. There are many possible investment conclusions one can draw. Here are mine:

1. We are no longer in a period where financial engineering and in particular leveraged finance are the primary source of investment returns. Where bonds are low yielding and equities are volatile, don’t be afraid of unlevered equity-only investments in high-quality projects. Be happy with a yield of 4-6%. You always have an option to raise debt in the future to leverage your returns. So what counts as a “high quality project”? Depends on many factors including time horizon and liquidity preference, but an example could be commercial real estate with high quality long-term tenants such as governments or highly rated corporates.

2. Infrastructure projects, particularly in the food and water sectors. But pick countries where the off-taker is likely to pay up for duration of the project. For example renewable energy projects in southern Europe came a cropper, because many relied on government subsidies for the duration of the project, and these subsidies were pulled when deficits needed to be cut. So, a good test would be “does the government or other off-taker really need the relevant infrastructure to be operational for its whole life ?”. Less important in advanced countries, where contracts tend by and large to be honoured.

3. And this leads us nicely to geographical considerations. Falling living standards in advanced economies does not translate into “don’t invest there”. Remember that big asset: the Rule of Law. And following Skene’s thesis, with banks pulling out of corporate lending, the opportunities for cash investors could be interesting. SMEs, perhaps listed on the smaller stock markets, may have a high amount of leverage on the books, find it hard to access primary equity capital, but have fundamentally strong operational cashflows. The opportunity for a cash buyer would be to take the company private, take the debt of the books and hopefully increase the efficiency and scale of the business with expansion capital. Exit by re-floating. Many such opportunities abound, particularly in Europe. Private Equity investing will mean what it used to, ie, taking over companies and managing or operating them better.

4. In terms of emerging economies, BRICs have been in and out of vogue over the past ten years. Continuing with the theme of fiscal strength driving economic strength, I would be looking at countries which growing populations from an already large based, strong fiscal positions and are capable of being a “self-sustained eco-system”, and some semblance of an industrial base. Within advanced economies, Australia looks interesting. The Gulf countries, (including, in the future, Iraq) are natural-resource backed economies with existing infrastructure and very little need to access international debt markets. There are some other examples in Africa, Latin America and Central Europe. A good starting point is the projected Debt/GDP ratios, which can be

found here.

I shall be developing these themes in future posts, but I would be very happy to engage in discussion, either via the comments section here, via email in private or through the various social media, Twitter and LinkedIn.

There is no Wikipedia link for this book. The Google Books link for the book is

here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed