If you haven’t read anything by Ferdinand von Schirach, a German crime writer and Munich lawyer, this is a good place to start, but do also check out The Collini Case, and The Girl Who Wasn’t There. His stories are translated from German into English, and the translator for Crime and Guilt is the recently deceased Carol Brown Janeway.

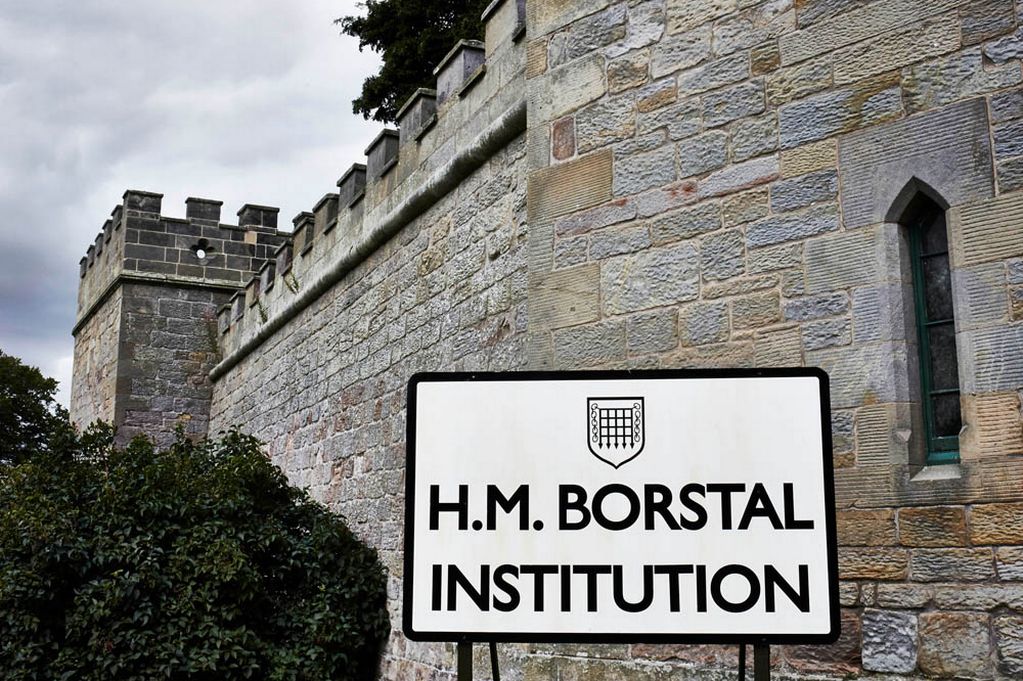

In a parallel with English Law the title hints at the two elements that must proved in a criminal court: first that a Crime was committed – the Actus Reus; and secondly that the accused had the Guilt or intention to commit – the Mens Rea.

This collection of short stories is a clear demonstration that neither Crime nor Guilt are clear cut – and just as importantly, the fine line before we all cross into one or the other, or as Schirach more eloquently puts it in his introduction:

“All our lives we dance on a thin layer of ice; it’s very cold underneath, and death is quick. The ice won’t bear the weight of some people and they fall through. That’s the moment that interests me. If we’re lucky, it never happens to us and we keep dancing.”

Take the story of the Ethiopian migrant who commits an almost comical bank robbery – “The cashier said she hadn’t felt at all afraid…[T]he robber had just been a poor soul, and more polite than most of her customers.”

As you hear about his life story, from childhood abandonment, to having every attempt to further himself blocked by the system or by prejudice, to his attempts to rebuild his life and live and Ethiopia – only to be thwarted by the bureaucratic machine:

“In the Middle Ages, things were simpler: punishment was only commensurate with the act itself. A thief had his hand chopped off. It was all the same, no matter whether he’d stolen out of greed or because he would otherwise have starved. Punishment in those days was a form of mathematics; every act carried a precisely established weight of retribution. Our contemporary criminal law is more intelligent, it is more just as regards life, but it is also more difficult. A bank robbery really isn’t always just a bank robbery. What could we accuse Michalka of? Had he not done what all of us are capable of? Would we have behaved differently if we had found ourselves in his place?”

“Miriam didn’t attend the main hearing. Her lawyer sent the divorce papers to the remand centre. Holbrecht signed everything without reading it.”

We are also treated to some pure comic moments, slapstick within the serious business of organised crime. Atris is a little slow, and has been left at back at their apartment by his partner in crime Frank do 2 things, and two things only. Look after the key to the locker where the booty is kept. And feed Buddy, Frank’s huge mastiff dog.

“He stared at the dog and the dog stared back. Frank hadn’t been gone for more than two hours and he’d already screwed things up: the dog had swallowed the key to the locker.”

Oh, and number three – don’t drive Frank’s Maserati. But, what will happen when Atris now has to drive buddy to the vet in the Maserati to get some laxatives ?

The weird and the wonderful all pass through Schirach’s office, and we chuckle. But it is often nervous chuckle, because there is a part of us that finds it scary, disturbing. We are somewhat cosseted these days, because we consume so much off the internet so when conspiracy theories, or worse, are casually bandied around it all seems so remote. We are safe behind our screens. But Schirach is a person who has come face to face with the real people behind the stories on a regular basis. What would you do if this guy walked into your office ?

“The camera. They inserted a camera in my left eye. Behind the lens. Yes—and now they see everything I see. It’s perfect. The secret services can see everything that Mohatit sees,’ he said. Then he raised his voice. ‘But they won’t get my secret.’ Kalkmann wanted me to bring charges against German Intelligence. And the CIA, of course. And former American president Reagan, who was responsible for the whole thing. When I said Reagan was dead, he replied, ‘That’s what you think. He’s actually living up in the attic at Helmut Kohl’s”

And that, really, is one of the hallmarks of a good author, someone who manages to get the reader to transport themselves into the story, and ask himself: “What would I do ? How do I judge this ?”.

And the remarkable thing for me the number of times I find myself rooting for the “criminal”, whether through empathy, morality, circumstance, or other mitigating circumstances. That is a common occurrence in works of fiction, and there are certain techniques that fiction-writers use to make the reader take sides. But these are real-life stories, and most of the stories jail sentences were handed out.

Crime, its practice, perception, prevention, policing, and prosecution represent the ultimate confluence of disciplines. Straddling emotion, (in)humanity, law, morality, philosophy and religion.

And overseeing all of these is Science.

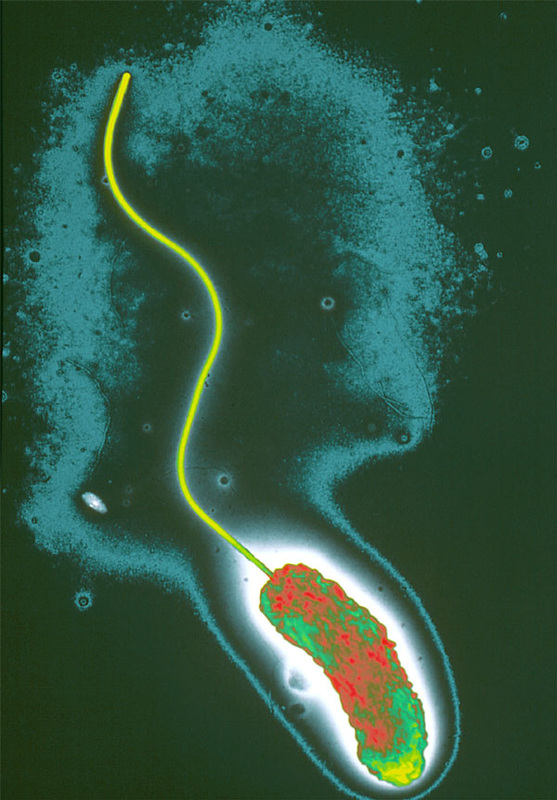

Science, that helps the perpetrator to commit the perfect kill:

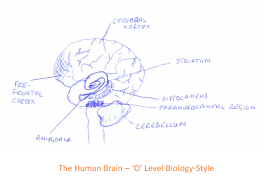

“The blow was precise, hitting the carotid sinus, which is a brief surface dilation of the internal carotid artery. This tiny location contains a whole bundle of nerve endings, which registered the blow as an extreme increase in blood pressure and sent signals to Lenzberger’s cerebrum to reduce his heartbeat. His heart slowed and slowed, and his circulation did likewise. Lenzberger sank to his knees; the baseball bat landed on the ground behind him, bounced a couple of times, rolled across the platform, and fell onto the train tracks. The blow had been so hard that it had torn the delicate wall of the carotid sinus. Blood rushed in and overstimulated the nerves. They were now transmitting a constant signal to inhibit the heartbeat.”

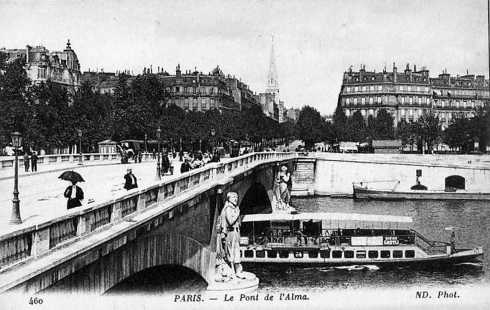

Or Science, the great arbiter of proof:

“[19 years later…] When the science had advanced sufficiently, the cigarettes in the dead man’s ashtray underwent molecular genetic analysis. All those who had been under suspicion back then were summoned for a mass screening.”

So that at the end of the day, some people when faced with incontrovertible facts of truth, or tragedy, or knowledge, take incontrovertible and irreversible actions:

“Everything was peaceful; it was Christmas. [she] was taken back to her cell; she sat down at the little table and wrote a letter to her father. Then she tore the bedsheet, wound it into a rope, and hanged herself from the window handle. On the twenty-fifth of December, [her father] received a call from the lawyer on duty. After he’d put down the phone he opened the safe, took out his father’s revolver, put the barrel in his mouth, and pulled the trigger.”

Many of the reviewers on the various blogs and forums describe this as a book they couldn’t put down until they finished it. Same here. The emotional journey of this book is intense, and when you get to the end you do want some explanations that maybe you can’t get, because you are not a judge, or a criminal lawyer, or a social worker, or a bank robber, or a policeman, or a victim.

So you look back to the beginning of the section “Guilt”, and there is the answer staring right at you.

In a quote from Aristotle:

“Things are as they are”.

There is no Wikipedia link to this book. The Google books link is here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed