I have always thought that learning a language, writing a good computer programme, and drafting a good contract involve essentially the same discipline (I suspect writing a musical score requires some of the same skills but I don’t know – can anyone enlighten me ?). Steven Roger Fischer takes the evolving and increasingly technical discipline of linguistics and language evolution, and gives us a quick tour in the History of Language.

First off, a small gripe. Split infinitives may or may not annoy people: linguistic conservatives want to preserve the “grammatical rule” that one should not put an adverb in between the two parts of an English infinitive. They would turn Star Trek’s “To Boldly Go” into “Boldly To Go.” And that, Mr Fischer, is the standard refutation that British children are taught in schools regarding the split infinitive rule. Churchill’s famous hypercorrective quip (“This is the sort of English up with which I will not put”), to which you refer (or should that be: “which you refer to” ? J ) is a clever refutation of another so-called grammar rule, but it’s not the split infinitive one, OK ? Right, rant over (though it does make one wonder whether there are any other errors in this book). The book is otherwise fascinating.

It has only been in the twentieth century that Western linguists were able to elucidate the principles of phonemics. But we find out in the History of Language that India’s earliest Sanskrit scholars had already developed the dvhani-sphota relationship in the first half of the millenium. Utterance was the dhvani; permanent linguistic substance, unuttered, was the sphota. Teaching us that language rules are inextricably linked to the philosophy, culture and religion of a society (the Hindu Vedas distinguish between word forms that are written, unwritten, and incapable of being written).

And just as amazingly these scholars adopted a highly efficient and systematic approach to documenting their grammatical forms that any proponent today of efficient computer coding would be proud of:

“Ancient Indian scholars appear to have been obsessed with grammar, seeking to state all rules in the most economical prioritized set: one commentator noted that saving half the length of a short vowel while positing a rule of grammar was ‘equal in importance to the birth of a son’. Word formation rules, applied in a strict set in aphoristic sutras, take precedence; in contrast, Sanskrit’s phonetic and grammatical description is almost wholly assumed.”

Through the study of linguistics valuable insights can be gained into the relationships between people of different regions that disciplines such as genetics are only today discovering. Take for example the recent genetic “discovery” that Y polymorphisms (extremely rare male genetic mutations), are relatively common both in Asian and Finnish populations. This would not be surprising to a scholar of the Finnish language. Since he will tell you that speakers of the Uralic languages in North-Eastern Asia becamce divided into two language families: Samoyed and Finno-Ugric (as an aside, Finno-Ugric is the source language for both Finnish (Finland) and Magyar (Hungary)).

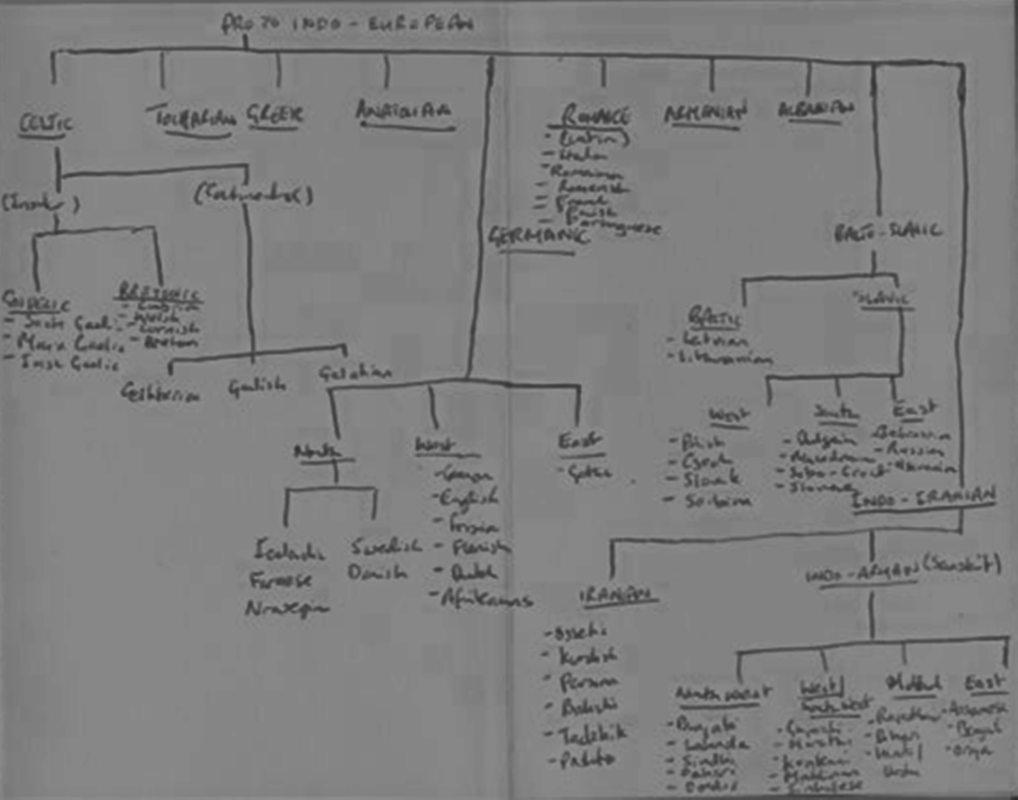

We learn how the discipline of modern linguistics was developed, particularly by scholars in the 19th Century. Franz Bopp (1791-1867) conducted a comparative study of the verbal forms in Sanskrit, Latin, Greek and the Germanic languages, and in particular the inflection (ie the systems of word endings which denote grammar). His principal work Vergleichende Grammatik extended this for all inflected forms, and he also carried out investigations into the relationships of the above with other languages such as Litauen, Armenian, Albanian, and the Celtic and Slavic languages. Hence all falling into the Indo-European family of languages. Bopp is today considered the founding father of the comparative study of the various Indo-European languages. The family tree below shows the principal ones and their groupings.

But what of other languages ? Fischer is unambiguously clear that the number of languages in the world will continue to reduce, of around 5,000 languages extant over the last 50,000 years, probably only 4,000 are spoken today, and Fischer thinks that only 1,000 will be spoken at the start of the 21st Century. Fischer postulates (not surprisingly) that English will be the dominant language in centuries to come (although doesn’t rule out some unforeseen occurrence which brings another rich-country language to the fore such as German or Japanese). The other two languages which will be globally prevalent are of course Mandarin Chinese and Spanish. And fast forwarding even further to days when we colonise Mars, we will no doubt see differences evolve between “Earthen English” and “Martian English”.

The benefits of standardisation of language are clear, as they reduce “transaction costs” of interacting across the globe. But of course, as Fischer points out:

“Despite the immediate gains language replacement brings, those who voluntarily give up their language invariably sense a loss of ethnic identity, a defeat by a colonial or metropolitan power (with concomitant sensations of inferiority) and a distressing defection from one’s sacred ancestors. This also entails the loss of oral histories, chants, myths, religion and technical vocabulary, as well as customs and prescribed behaviour.”

This is a short book, and hence very readable, or indeed one that you can dip in and out of at leisure. The section on animal communication is particularly fascinating for example, and it can be read entirely in isolation. Did you know that the blue whale emits probably the most powerful sustained sounds known on Earth ? Its 188-decibel “song” is detectable for hundreds of kilometres, and the perfectly timed notes are emitted at intervals of 128 seconds, or if there is a pause, at exactly 256 seconds. Likewise humpback whales emit “long love songs” used for mating. These are regular sequences of sounds varying widely in pitch and lasting between six and thirty minutes. But when you record these songs and speed them up around 14 times, they apparently sound remarkably like birdsong !

If I had a criticism of the book it would be that it is longer on Proto-Indo European and shorter on Semitic and Asiatic languages, and hence arguably reflects a linguistic-cultural bias of its own.

But that is a minor quibble as it is full of pointers for anyone who wants to study more in this area.

There is no Wikipedia entry for this book. The Google Books link is here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed