This is the third in an occasional series, Lessons from Fiction. The Breath of Night is a new book by English author Michael Arditti. It has been promoted, sorry, reviewed, extensively in the mainstream media already, such as the Spectator, the Independent, the Scotsman, the Telegraph, the Guardian, and even the Daily Mail Online. With such revered Thought-Leadership behind it, I was curious to see what all the fuss was about.

Arditti raises important questions about the role of the Church and whether it should be more overtly political. In this article I would like to explore that suggestion. My conclusion is that economic intervention is more effective than political intervention and I have put some numbers around one of the examples in the novel to illustrate the point.

If you have travelled extensively in developing countries (is it ok to use that expression any more ? I still like “Third World”, but that’s definitely off limits now), you will feel the smells, the sounds, the taste, the moisture, the “vibe” of Philippines, even if you haven’t been there, because it is just like all those other countries you have visited.

“The pavement was almost as tricky to negotiate as the road. Ahead of them a man, wearing nothing but shorts, soaped himself nonchalantly as if he were in his own bathroom. To his left, three men played cards on an oil drum surrounded by a jeering an gesticulating crowd; to his right three women sat stirring brightly coloured stews an bubbling pots of rice while their children frolicked at their feet, perilously close to the wobbly stoves. All around them were stalls selling food, drink, scarves, T-shirts, sunglasses, lighters and pirated DVDs.”

Scratch below the veneer of the (faux-)colonial hotels and malls catering to the whims of the newly-minted Global Traveller, and you find an incredibly complex society.

Or, I should say, “societal structure”. An anthropological order that existed long before the colonial masters arrived and departed and continues to survive long after the arrival of “independence” and “democracy”.

“Nothing in this country is the way it looks. You think that because the Filippinos have Spanish names and speak English that you understand them. Big mistake !”.

In Arditti’s model, there are essentially five main actors and somehow, like spheres rotating around a central gravitational force, they seem to maintain an equilibrium with respect to each other: the Elite Landowners, the Masses (workers in the cities and workers on the land, if they can get work), the Government, the Church, and the “communist” Freedom Fighters.

Revolutions and overthrows of the incumbent government come and goAquino

for Marcos, in the period covered by the book), but not much really changes:

“The most notorious Marcos ministers have been removed, but by and large the faces in both the Senate and the House of Representatives remain identical. The army has been granted immunity for all its crimes during the State of Emergency”

Basically the Elite Landowners, control everything, and maintain their power

structures through the tacit or not-so-tacit government of the day.

The personification of the landowner is the haciendo, the proprietor of the hacienda farm estate, acquired originally by the conquistadores. The haciendo plays a benevolent role in society, because he provides work for tenants on his farm:

“Don Florante is reputed to be one of the more enlightened landlords. He takes a paternal interest in his tenants, advancing them money for seeds and tools, selling them cheap rice during droughts, and standing as godfather to their children (which, here, involves far more than remembering them at Christmas and birthdays).”

And the tenants themselves recognise, accept and even embrace their own role:

“The farmers have a sense of indebtedness that goes way beyond indenture. They feel an almost mystical bond to the haciendos”

Which is unfortunate, because economically, not surprisingly they are stuck:

“The share tenant is vulnerable to the proportion of his harvest due to the landlord, and the leasehold tenant to a fixed rent that takes no account of the all too frequent crop failures.”

I was fascinated by this statement, and since this article about lessons from fiction I would like to alight from the train here and just look into this a little it more: we will return to the Church and the Freedom Fighters later.

Let’s analyse the above tenancy arrangements by putting some numbers on them. These are unresearched assumptions, but they should give us a flavour of what’s going on. I would be very happy to hear from readers who would like to challenge the assumptions or to provide better data to feed into the models.

Imagine a household which is a tenant on the hacienda, and which is a family of 5. They harvest the land and for say four months of the year it produces an income. Based on the Philippines’ 2011 GDP per head of $2,400 I have assumed 3 productive members of the household, so a total of $7,200 produced by the household during the year. Assume that the household’s monthly expenses are $2 per person per day and 30 days per month. Thus the monthly expense is $2*5*30 = 300, or $3,600 per year.

What happens under the first version described above, where the landlord takes a percentage of output ? Let’s assume the landlord takes 45%. Why have I chosen this number ? Well, without doing detailed research I have made the following assumption. It just so happens that at 45% the household is just about able to make some savings at the end of the year, amounting to $360. The landlord is the one with all the information: if he sets the percentage too low he is not maximising his profit; if he sets it too high, the tenant has no incentive to work hard. The tenant works the land in the Hope that he will put aside a meagre amount every year, and one day his family will be able to afford an education, or a life in the city. The landlord is the one dispensing the Hope.

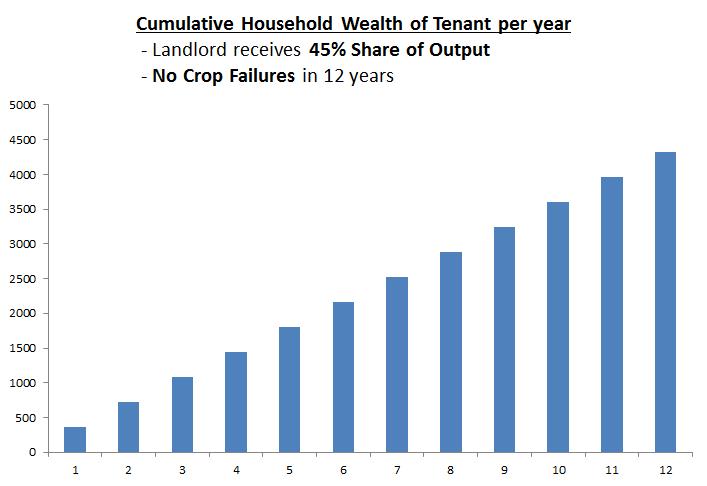

And indeed it seems to work. Look at Chart 1. Lo and behold every year the household’s wealth increases, up to a respectable $4,320 after Year 12.

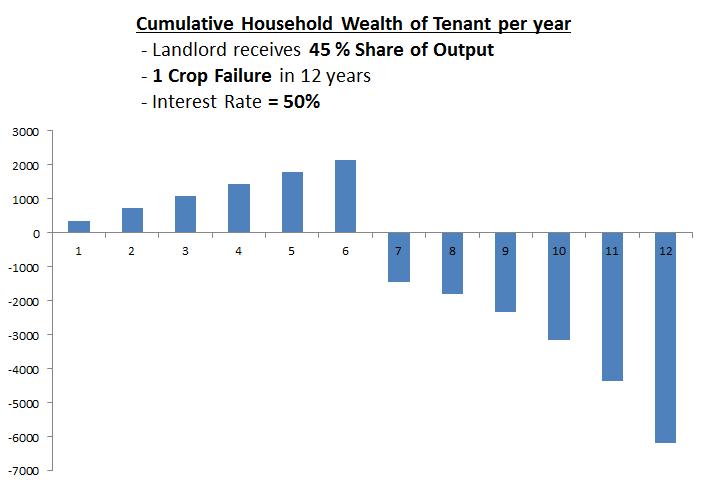

What happens to our tenant household ? Well, on the one hand their savings will be wiped out, and the household will be put into debt. Let’s assume that they can borrow the money, but will need to pay an interest rate of 50% pa (a reasonable assumption, I think). Look what happens to their finances in Chart 2. Ouch. By the end of Year 12 our household is over $6,000 in debt.

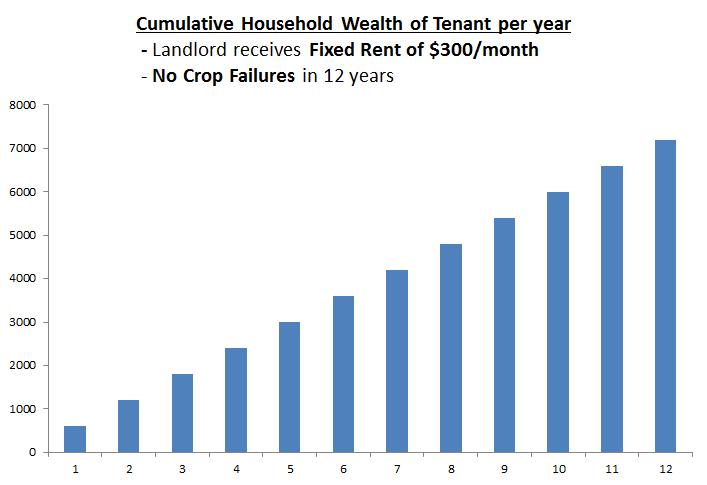

Is it any better for the tenant to adopt the second model, and pay a fixed rent ? Suppose the landlord charges a fixed rent of $250 per month, regardless of output. In this case, the wealth accumulation is even better, there is more Hope for the tenant. Chart 3 shows that the family accumulates $7,200 at the end of Year 12:

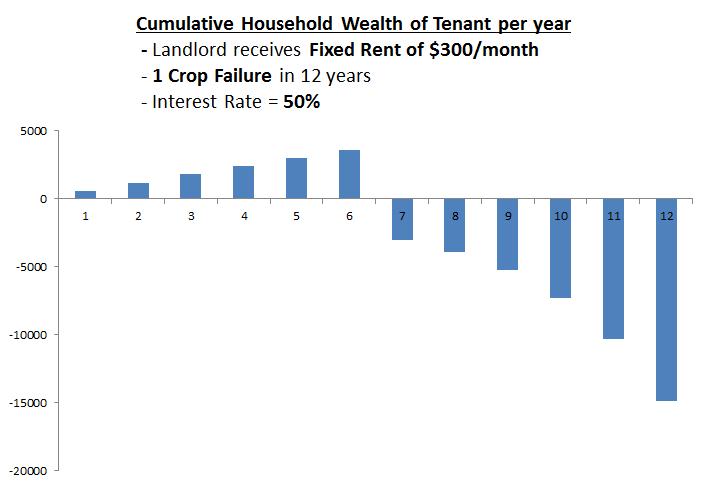

But look what happens (Chart 4) when there a crop failure. The rent still has to be paid, so an even bigger liability is incurred when the Year 7 income disappears. And the debt spiral at 50% pa interest rates take the household to a whopping $15,000 in debt by Year 12, although you would imagine they will have been evicted into destitution long before that.

In the novel Arditti examines in depth the role of the Church within a society such as this. Julian Tremayne, a Catholic priest of mid-ranking English aristocratic blood, leaves his home country in the 1970s and sets out for the Philippines to take up a posting there as parish priest. Over time, his pastoral duties bring him into contact with exactly the type of people described in the example above. Initially he plays the role that is expected from him, preaching to the congregation according to local custom, and providing food, shelter, medicine and money for those in extreme need. In this role he is very much part of the Church Establishment, which above all wants to maintain cordial relations with all factions in Philippine society.

However, over time, Julian develops a closer relationship with the country’s

Freedom Fighters, the New People’s Army or NPA, who are engaged in violent and revolutionary struggle against regime of the day (first Marcos, then

Aquino). At first it is logistical support that Julian provides (e.g. transport and shelter). But he struggles increasingly with his conscience and feels that the Church as an institution should engage actively in the freedom struggle:

“Poverty and oppression endanger the soul [of the rich] along with the body [of the poor]. A woman whose children are starving may break the seventh commandment, just as a man driven mad by tyranny and injustice may break the fifth. So as a priest, I’m obliged to concern myself with the here and now as much as the hereafter; indeed, the two are inexplicably linked. If a priest is to stand in the person of Christ, he can’t avoid being political.”

Hence he becomes more actively involved with the NPA (it is ambiguous as to whether he actually engages in any acts of violence or terror) and is eventually murdered in 1989.

The novel’s other protagonist is Phillip Seward, a young and out-of-work Art Historian, who has an emotional connection (you need to read the book to know why) with Isabel, the niece of Julian Tremayne, and her husband Hugh (who happens to also own a trading company that has extensive commercial interests in the Philippines). Isabel was particularly close to her uncle Julian.

Isabel manages to persuade Hugh to bankroll an assignment for Phillip to the Philippines to report on an investigation that is underway there into whether Julian satisfied the requirements for being declared a saint. Progress on the investigation has been painfully slow and Isabel feels that Phillip would be able to provide an objective view as to what is going on, and maybe to speed it up a little.

The story flips between Phillip’s 21st century induction to the country, as he uncovers Julian’s story, and the Julian’s letters, which tell his own story 30 years earlier.

Arditti wants us to question the role of the Church, and whether it should proactively align itself with revolutionary causes. Is the Church by definition a political institution that must fight to prevent poverty as well as treating its symptoms ? Certainly in previous centuries, both the Protestant and Catholic Churches have been more explicitly combative.

The author himself seems not sure of the answer:

“I think that’s what Julian objected to. He didn’t want a world that was split into masters and servants. No, he and his friends wanted revolution. They were terrorists, even if they had no guns – and believe me, there are many who swear that they did. Suppose they had succeeded, what then ? They get rid of Marcos and end up with Mao or Pol Pot. Do you think the people would have been happier with that ?”

Amongst all this ambivalence about political intervention, may I suggest an alternative route for institutions with the means, such as the Church. That is, that rather than pick political fights which may lead to worse outcomes and more destruction, such institutions can provide real economic assistance.

Let’s go back to the example that we analysed above. The astute reader will have noticed what the real problem is (actually, there are two – answers on a postcard, please). The real problem is the interest rate that the household pays when it goes into debt.

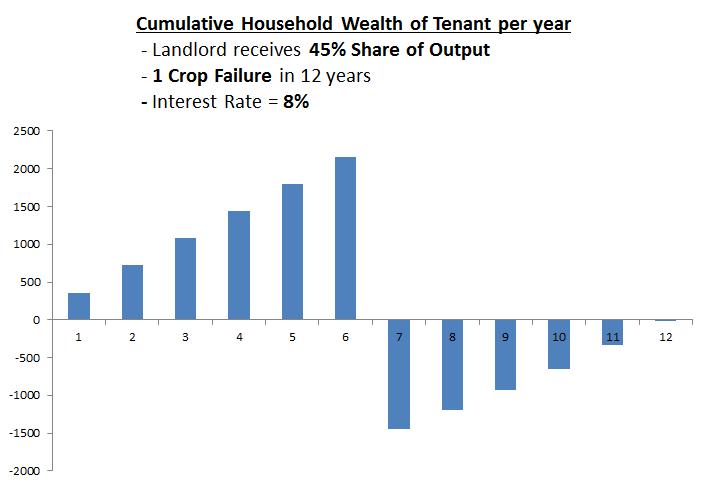

A somewhat topical issue on which the Church of England has recently expressed a view as well. Now, look what happens if the tenant can have access to cheaper credit, say at an 8%pa interest rate. Chart 5 applies this to the first example (tenant paying a proportion of output), but I assure it works for the second type as well.

Et voilà ! A steady recovery back to prosperity.

Now that really would be putting its money where its mouth is.

There is no Wikipedia entry for this book. The Google Books link to the book is here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed