My one liner: Nobel Prize winning economist. A comprehensive survey of the great theorists' competing notions of justice, concluding that a system based on Social Realism (or taking society as it is) is preferable to constructing institutions of justice in a vacuum (“Transcendental Justice”).

Framing the debate on the nature of justice, Amartya Sen provides a practical illustration, which he calls Three Children and a Flute, in the Introduction of the book: Imagine which of three children Anne, Bob and Carla should get a flute about which they are quarrelling. Anne claims the flute on the grounds that she is the only one who knows how to play it. Bob, on the other claims the flute because he says that he is the only one of the three who is so poor that he has no toys of his own, so the flute would give him something to play with. Carla then intervenes and says that it was she who made the flute with her own painstaking labour, and just as she finishes her work “these expropriators came along to try to grab the flute away from me.”

It is clear that theorists of different persuasions would give the flute to different

candidate. The economic egalitarian would give it to Bob, on the basis that poverty and inequality should be reduced. The utilitarian hedonist “would face the hardest challenge”, but would be persuaded to give it to Anne, as her pleasure would be greatest from owning and playing it (though he would recognise that Bob’s incremental pleasure in owning it may outweigh this). The libertarian would of course have no hesitation in awarding it to Carla.

Amartya Sen’s credentials in leading us towards new theories of justice are of course impeccable, so this is a book that we have to pay attention to. “Transcendental Justice” is the term he gives to the theories, which seek

to prescribe an institutional framework to the ideal form of justice, a sort of

build-it-and-they-will-come approach. Sen uses the work of John Rawls as his "departure point". Sen was a student of Rawls, and whilst he acknowledge Rawls’ contribution to modern thinking on justice, he also considers it to be too rigid. Rawls’ concept of “Justice as Fairness” is centered on a requirement of “primordial equality”, namely that the “parties involved have no knowledge of their personal identities, or their respective vested interests, within the group as a whole. Their representatives have to choose under this ‘veil of ignorance’”. The primordial equality requirement then goes on through a chain of reasoning to determine the types of institutions that would be required to deliver it.

Sen is more drawn to the “Social Realisation” school of justice. This is more concerned with justice as resulting from “actual institutions, actual behaviour and other influences.” These concepts are to found in Smith, Condorcet, Bentham, Wollstonecraft, Marx, and Mill. In Sen’s words all of these thinkers, though having very different ideas about the demands of justice were “all involved in comparisons of societies that already existed or could feasibly

emerge”.

Sen is able to draw on Indian notions of justice, both from Sanskrit texts on jurisprudence and also from the Hindu epics of the Bhagavad Gita and the Mahabharata. So in Sanskrit literature, niti and nyaya both stand for justice. Niti signifies organisational propriety (and hence more akin to the transcendental institutionalism) and Nyaya which stands for a comprehensive

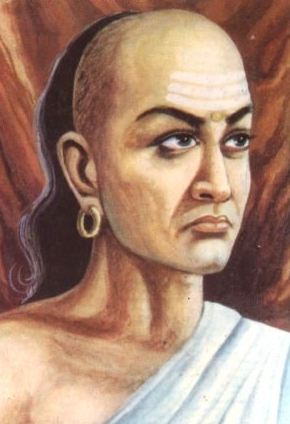

concept of realised justice. And he draws on examples of Eastern emperors who have come to symbolise one or the other. Contrast the practical, societally relevant forms of justice practised by both Ashoka (a Hindu) and Akbar (a Muslim) on the one hand, with the much more prescriptive format expounded by Kautilya (a must-read by the way, if you want do a compare and contrast with Machiavelli), the latter having little faith in the ability of his subjects to make such decisions for themselves.

The arguments that Sen draws us towards are those of Adam Smith in his Theory of Moral Sentiments. Smith invokes the concept of an “impartial observer” who can adjudicate on fairness given the world as it is, and who can take into account factors and opinions which are not merely present within the immediate community but which are geographically distant, but nevertheless relevant. Sen believes that this is a more relevant way to approach justice in an interconnected world in which we grapple issues such as global terrorism and the financial crisis.

Overall, there is as you would expect real intellectual substance in this book. But it is highly readable, and more importantly highly relevant for how we think about what constitutes realistic justice.

Here is the Wikipedia link to the book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed